This past week my tutor at the school placement caught up on the correction of the students' coursebooks. She told me that in the training courses and seminars she had attended regarding this methodology (Eleanitz, designed by ikastolak) they told her that the teacher wasn't meant to do any correction work on the students' activity books, but she felt better by doing so. She also told me that the number of errors she found were unbelievable, taking into account that all exercises were corrected in class after the students finished them.

On Friday afternoon, in the LH4 lesson, when the students took their coursebooks to complete an exercise on telling the hour in English, I noticed that she corrects using a green pen. I found it amusing. She told the students that they had to pay more attention in class, because she had found a lot of mistakes. By the way, often we correct exercises before most of the children have time to finish them, because we are pressed with time, because there is a programme to complete...

I had noticed that one of our teachers at university uses the green pen too. To be honest, the teacher at university mostly writes her reflections on the diaries we write, more than correcting mistakes, although she does some of that too.

Apparently, green is the new red. I have been thinking about it over the weekend, and I was surprised to see that I got really mad at times thinking things like "it's the same old bullshit, just disguised in green!". I didn't think I had that kind of resentment in me towards the red pen (in my childhood?), but there seems to be something somewhere...

I hate sugar coatings and disguises of that sort. If you are going to point the accusing finger at students, you might just as well do it openly and be honest with yourself, using a thick red marker. And if you really want to do things differently, then squeeze your brain a bit more than just changing the colour of a pen.

On the other hand, we have been told that when it comes to learning a language, fossilised errors need to be corrected, so why not use the red pen on those, and only on those? Of course, that is much more difficult than correcting all mistakes in green...

If a teacher has managed to create a positive atmosphere, the correction of errors is something that can be done naturally, because there are many ways to do it. I practised some last Friday, while students were doing their telling the hour exercises, and it's not that hard. Most of the times a question is enough ("are you sure about this?" or "if you have said this in the previous exercise, shouldn't you be saying something else here?"). Even a red pen will be taken in a good way, if you have managed to create a positive atmosphere before.

This school placement is being great, because it is creating many "disbalances" in me in a constructivist sense, and I feel a bit restless because I haven't balanced back yet. A good sign: it must be that I am learning.

2014/11/30

Second week in my school placement

I am slowly becoming more familiar with the school, both the building itself and the staff, so I know my way around a bit better now. I also got to know another part of the “community”, the microbial one, and as a result I caught a nice cold. I guess it is the price you have to pay in exchange for the school placement.

This week I have continued attending my English lessons and I have just begun reading the Hocus and Lotus teacher’s guide for LH1 and LH2. Amagoia, my reader, and I are attending different grades in LH, so we will be able to complement each other, but we will not have a chance to contrast ways of applying the same methodology in the same grade but in different schools, which is a shame.

Well, this week I want to talk mainly about what I have seen so far in the LH lessons. One thing I like a lot about the ways of doing of my tutor is the treatment of error, for example when they use flashcards to review vocabulary. She will ask one child what the image in the flashcard represents, and if they don’t know, they are simply asked to give the chance to somebody else to guess. It is a neutral treatment of error, and that is good.

During these two weeks several activities performed in the LH lessons have reminded me of the task feedback circle by Jim Scrinever, which we learned about during the first term in our Minor. Sometimes the teacher has explained the task clearly before starting, especially in LH1 and LH2, but there was a reading task in LH4 where there was no explanation whatsoever on the task which was going to be done afterwards which left me thinking on this issue.

This is what we did in class: the teacher explained that we were going to read the story (Sorry, I’m late!) aloud taking turns. The week before we had listened to the story on the CD, and students had been working on the story previously too. So, children started reading one page each (each page has a short paragraph and sometimes a dialogue inserted in the drawing that goes with it), following the class list, while the teacher took her notebook to take notes as they read (I am sure children notice such things, because the teacher doesn’t usually hold her notebook, and I think it helped to create an “exam atmosphere”). When they finished reading, the teacher said: “now that we have the story fresh in our minds, we will do the essay activity”. This is an activity where students have to summarise the whole story in four blocks. Each of the blocks has one drawing taken from the book and some lines underneath for students to write, as well as a couple of balloons for dialogues in the drawing. The students have a draft copy in their books to do a group draft, and after the teacher corrects it, each one of them copies the final draft on their book. They had already done this activity for the previous story, and the teacher had told me that it was the most difficult activity.

So, children started writing their summary and the teacher and I monitored to give help. When they asked me for help, I realised that although I had been following the story as they read, I hadn't focused my attention in the way that this task required. So, in order to be able to help them, I had to take one of the books in my hands and read over it. Children were confused because the first block included the image in the first page of the story, where the two main characters were walking on the street with no balloons for dialogues, but in the summary block, this image had balloons. They kept on saying that they didn't know what to put there, because in that picture the characters weren't speaking. I tried to explain that in that first block they had to summarise several pages of the story, showing them the pages concerned; and that they understood.

The problem is that we did the reading without knowing what to listen to, what to look for, and we weren't prepared for the task.

One thing that struck me about the listening activity we did the previous week on this same story was the following: the CD recording has a tic-tac sound which alerts students that they have to turn the page, so they receive a guide while they are reading. Still, I would find it helpful if they actually followed the text with their fingers as they listened, because I noticed that some of them get lost and are only listening to the tic-tac sound to know when to turn the page. I must ask I tutor why they don't use that resource.

Another thing I like a lot about the ways of doing my tutor uses is the fact that students correct each other when the helper does the daily routines. The helper writes the date on the board, and the rest of students spot mistakes and correct them.

I already talked about the short role plays they perform in class, 2 to 5 students at a time while the rest watch. The teacher uses the same procedure always: after having decided who plays which role, the teacher performs the part of each character, and then she plays the CD while students perform. Children usually have masks to get into their character. What I find strange is that children only do the gestures, but don't say the dialogue along with the voice in the CD, which is a shame. Sometimes, after they have finished the role play, as students go back to their seats, they will say their dialogue, but the teacher doesn't acknowledge it. I wonder what could be done in order to promote a more active role by students in these sort of activities.

During these first weeks, as I mainly observe, even though I also monitor and give help, I have been trying to spot things which work and thing which don't work, and thinking of why that is. There was an activity in LH2 where children had to write a short dialogue between two characters of their story (the lion and the rat). The teacher performed the dialogue and she wrote it on the board (“I’m a lion. I like meat”, “Please, don’t eat me!”), but she said she would erase it in a short while (which got students very upset, by the way). After she erased it, children started writing it on their books. When they said they didn’t know how to write lion and meat, she reminded them that they had those words in their dictionary. The dictionary is a task they had done the previous week, when they cut out several images from one page and glued them on another page, which had some squares drawn, with the names of each image. Children had to match each image with the right text, and glue it. I think that part of the reason why children didn’t memorise the words has to do with the way we did the activity: first, the teacher asked them to number each square, and then she went through the images in the other page, so with the help of all we worked out which number they had to write on the back of each image. Then, children just had to match numbers. Their attention was focused on form, but not on words, but on numbers; therefore, they didn’t work on memorising words.

The last words will be on myself. I have also been trying to observe myself and reflect on that, although it is much harder to do it on myself than on others if I don’t record it. This week, one of the days I was with the LH4 class, I realised that during the monitoring of their activity writing the summary of the story, I spelled “together” twice to two members of the same group, I spelled “wave” in another group, and did some more spelling for others. When we finished, I asked to myself what I had been doing that day, and I realised it was very far from what I think I should be doing as an English teacher. I can’t be a walking dictionary, giving answers; I should find ways for students to sort out their own answers and help them on that. So, I had done no scaffolding at all (other than trying to create a good atmosphere and positive interaction). So, in the next class I had with that group I tried to change my way of helping them, while they were learning to tell the hour in English, and pointed them to using the examples they already had in the book to find out their own answers.

Well, that’s it for this week. Next week I want to talk about something which bothers my tutor: even though she asks students to do some tasks in group, they do them individually. I have been watching them and trying to think of reasons why that happens and things that could be done to change it. Oh, and I will also talk about my first lesson: I will be performing a lesson in HH4 this coming week. I have already designed it and prepared the material I need, and I plan on recording it to analyse it afterwards.

Storytelling vs. using stories

This week I have also been thinking about the question that my school placement tutor posed when we last met: what is storytelling?

I will use a couple of quotes from Daniel Pennac's book Como una novela to summarise what I have come up with as an answer:

So that is storytelling, and using stories for educational purposes is something else.

I guess my undergraduate dissertation will deal with the use of stories to teach foreign languages, especially English. What a bummer!

I will use a couple of quotes from Daniel Pennac's book Como una novela to summarise what I have come up with as an answer:

El verbo leer no soporta el imperativo. Aversión que comparte con otros verbos: el verbo "amar"..., el verbo "soñar"...If that wasn't clear enough:

Claro que siempre se puede intentar. Adelante: ¡Ámame! ¡Sueña! ¡Lee! ¡Lee! ¡Pero lee de una vez, te ordeno que leas, caramba!

Sin saberlo, descubríamos una de las funciones esenciales del cuento, y, más ampliamente, del arte en general, que consiste en imponer una tregua al combate de los hombres.

El amor adquiría allí una piel nueva.

Era gratuito.

Gratuito. Así es como él lo entendía. Un regalo. Un momento fuera de los momentos. Incondicional. [...]

Como precio de este viaje, no se le pedía nada, ni un céntimo, no se le exigía la menor contrapartida. Ni siquiera era un premio. (¡Ah, los premios..., los premios había que ganárselos!) Aquí, todo ocurría en el país de la gratuidad.

La gratuidad, que es la única moneda del arte.

So that is storytelling, and using stories for educational purposes is something else.

I guess my undergraduate dissertation will deal with the use of stories to teach foreign languages, especially English. What a bummer!

Continuing gathering literature

This week I have continued gathering recent articles that might be useful for my undergraduate dissertation. I must admit that some of the articles that have attracted my attention are not specifically on using storytelling in the English classroom. For example, I have been reading very interesting things on the use of the teacher's autobiography to teach English as a second language, on case studies about the use of bilingual narratives in the acquisition of English as a second language and about trilingualism.

Honestly, I don't know how these things will fit into my dissertation, but I believe that letting myself wander off a bit is good. At the end of the day, mixing the top-bottom and the bottom-up approach can be useful in the dissertation, at least the way I see it. By that I mean that not only do I have to look for literature on the topic of my dissertation, but also find links between things that apparently are not strictly linked to my topic but have caught my eye and my dissertation.

After I finish looking for journal articles, I will go to both the university's and HABE's libraries to look for books on my topic. And when I do that, I think I will be ready to start reading and writing. I will most probably need to do some more literature search after I start reading, but it will most probably be more specific.

From what I have seen so far, there seems to be an awful lot going on around digital storytelling, which doesn't look too appealing to me, to be honest. Besides, during my school placement it doesn't look like I'll have many chances to go into that. So, I'll have to see if I get into digital storytelling or I skip it altogether.

Honestly, I don't know how these things will fit into my dissertation, but I believe that letting myself wander off a bit is good. At the end of the day, mixing the top-bottom and the bottom-up approach can be useful in the dissertation, at least the way I see it. By that I mean that not only do I have to look for literature on the topic of my dissertation, but also find links between things that apparently are not strictly linked to my topic but have caught my eye and my dissertation.

After I finish looking for journal articles, I will go to both the university's and HABE's libraries to look for books on my topic. And when I do that, I think I will be ready to start reading and writing. I will most probably need to do some more literature search after I start reading, but it will most probably be more specific.

From what I have seen so far, there seems to be an awful lot going on around digital storytelling, which doesn't look too appealing to me, to be honest. Besides, during my school placement it doesn't look like I'll have many chances to go into that. So, I'll have to see if I get into digital storytelling or I skip it altogether.

2014/11/23

First small steps in my undergraduate dissertation (GRAL)

At the beginning of the term, we chose the topic and our GRAL tutor, and after that we got tangled in assignments and regular coursework. As a result, I haven't been able to do anything on my GRAL until this week, when after having finished this term's lessons we started our third school placement.

So far, I have read the GRAL guide again; I have read a bit of the website our teachers have created to give us support to do our dissertation; I have begun to create my document template for the dissertation (our GRAL tutor provided us with one, but since I am used to creating my own, I rather do it from scratch), downloaded the university logo and read about the university's typo (I wonder if we will be allowed to use it, as it is not mentioned in the GRAL guide); I have also installed the application which will allow me to search in our university's databases from my computer at home, something that I hadn't done in my new computer yet; and have searched on my topic in the ERIC database.

The most interesting things I found in the GRAL guide, besides the specifications for the written report and the poster of my future dissertation, were these two:

Bearing in mind that my dissertation topic is storytelling (vast and vague, so far), I have been thinking about the questions that could be the starting point for it. For now, this is what I have come up with:

I am aware that while questions 1, 3 and 4 help narrowing down the topic, question number two broadens it. Therefore, it is an issue I should not develop in depth, but I think it is useful to set the role of storytelling in education, and then narrow the topic down to storytelling related to language acquisition.

I am also aware that there should be a number 0 question: what is storytelling?, which is tricky itself, because storytelling is a common word whose meaning we take for granted, and those are usually the words most difficult to define. That was the first question my school placement tutor at university threw when we met to discuss how to link this last school placement with the dissertation, and I realised I had no answer for it.

Obviously, I have not narrowed down the topic enough yet, but I hope that once I start reading the articles I have downloaded so far, I will see things more clear.

Writing the questions has arisen a terminology problem: foreign language learning?, second language acquisition?, foreign language teaching? Which should I use in my dissertation? I guess it is time to ask my teachers guidance on whether they are equivalent terms or they are related to specific points of view.

The website our teachers created around the dissertation took me to action research regarding the options we have on the methodology for our research. Now, this is a very interesting topic, which I came across in my first year of the degree. In the unit on the theory and history of education we had a really good teacher who got us involved in cooperative learning, so each of us had to learn on a particular author and teach the rest of our classmates on it. I had never heard about any of the authors then, and when it was my turn to choose, I took John Elliott by chance. It was one of those enlightening coincidences, as I found the action research he advocated very inspiring. It is on number 37 of my long list of concepts and authors which make up my personal map on education (it might be a good idea to try to complete it and give it a more appealing form by the end of this academic year, by the way). Coming back to the GRAL guide, in my opinion this is what our School of Education means when they say they want to create reflective teachers. So, there I have another ingredient for my dissertation, which I will have to bear in mind while I do the literature review on my dissertation topic.

So far, I have read the GRAL guide again; I have read a bit of the website our teachers have created to give us support to do our dissertation; I have begun to create my document template for the dissertation (our GRAL tutor provided us with one, but since I am used to creating my own, I rather do it from scratch), downloaded the university logo and read about the university's typo (I wonder if we will be allowed to use it, as it is not mentioned in the GRAL guide); I have also installed the application which will allow me to search in our university's databases from my computer at home, something that I hadn't done in my new computer yet; and have searched on my topic in the ERIC database.

The most interesting things I found in the GRAL guide, besides the specifications for the written report and the poster of my future dissertation, were these two:

- One or more questions should be the starting point for the dissertation.

- The School of Education where I study my undergraduate degree in pre-primary teacher education aims to create reflective teachers.

Bearing in mind that my dissertation topic is storytelling (vast and vague, so far), I have been thinking about the questions that could be the starting point for it. For now, this is what I have come up with:

- How does storytelling help language acquisition?

- What other roles does storytelling play in children's development?

- What are the main trends regarding the use of storytelling in English teaching/learning?

- What ingredients must storytelling have in order to maximise opportunities for language acquisition in general, and foreign language acquisition in particular?

I am aware that while questions 1, 3 and 4 help narrowing down the topic, question number two broadens it. Therefore, it is an issue I should not develop in depth, but I think it is useful to set the role of storytelling in education, and then narrow the topic down to storytelling related to language acquisition.

I am also aware that there should be a number 0 question: what is storytelling?, which is tricky itself, because storytelling is a common word whose meaning we take for granted, and those are usually the words most difficult to define. That was the first question my school placement tutor at university threw when we met to discuss how to link this last school placement with the dissertation, and I realised I had no answer for it.

Obviously, I have not narrowed down the topic enough yet, but I hope that once I start reading the articles I have downloaded so far, I will see things more clear.

Writing the questions has arisen a terminology problem: foreign language learning?, second language acquisition?, foreign language teaching? Which should I use in my dissertation? I guess it is time to ask my teachers guidance on whether they are equivalent terms or they are related to specific points of view.

The website our teachers created around the dissertation took me to action research regarding the options we have on the methodology for our research. Now, this is a very interesting topic, which I came across in my first year of the degree. In the unit on the theory and history of education we had a really good teacher who got us involved in cooperative learning, so each of us had to learn on a particular author and teach the rest of our classmates on it. I had never heard about any of the authors then, and when it was my turn to choose, I took John Elliott by chance. It was one of those enlightening coincidences, as I found the action research he advocated very inspiring. It is on number 37 of my long list of concepts and authors which make up my personal map on education (it might be a good idea to try to complete it and give it a more appealing form by the end of this academic year, by the way). Coming back to the GRAL guide, in my opinion this is what our School of Education means when they say they want to create reflective teachers. So, there I have another ingredient for my dissertation, which I will have to bear in mind while I do the literature review on my dissertation topic.

2014/11/22

First week in the 3rd practicum

Our practicum tutor asked us to write a weekly report on our practicum. Then, each one of us will read somebody else's week report, comment on it, and then the writer will further reflect on the comments which have been made.

I will bring here just the first part; what I write every week, because I think it should be in my blog, like the diaries of my two previous in-school trainings.

I will bring here just the first part; what I write every week, because I think it should be in my blog, like the diaries of my two previous in-school trainings.

Well, there are so many things that could be said, but I don’t want to make a never ending diary, so I will try to be selective.

First of all, I will start with my planning. So far, I will be attending lessons for one group in each of these levels: HH4, HH5, LH1, LH2 and LH4. The school has three groups per level, so I have decided to choose one in each level. There are three English teachers: my tutor, who works full time and holds a permanent position for three years now, and two other teachers who work part-time (one of them takes HH4 and HH5, while the other one teaches in LH5 and LH6). The one who teaches in HH is new and is taking over a teacher who is on maternity leave.

I will maintain this planning for a few weeks, to get an overall idea of how they work, and maybe later on I will concentrate on HH4, HH5, LH1 and LH2, taking part more actively in lessons with more than one group per level. That is the plan, but we will see how things develop in the forthcoming weeks.

My tutor takes the English classroom and has all her lessons there, while the other two teachers perform their lessons in the regular classroom of each group. Here are some pictures of the English classroom, which is spacious and full of light.

This is a general view of the classrooom

Another general view, with all the students’ coursebooks stored in the back

The blackboard, with the teacher´s desk on the left

Some useful sentences and structures on top of the board

Class lists on the bottom, to keep track of the helpers; and material for the daily routines

Hocus and Lotus poster for LH1 and some other material

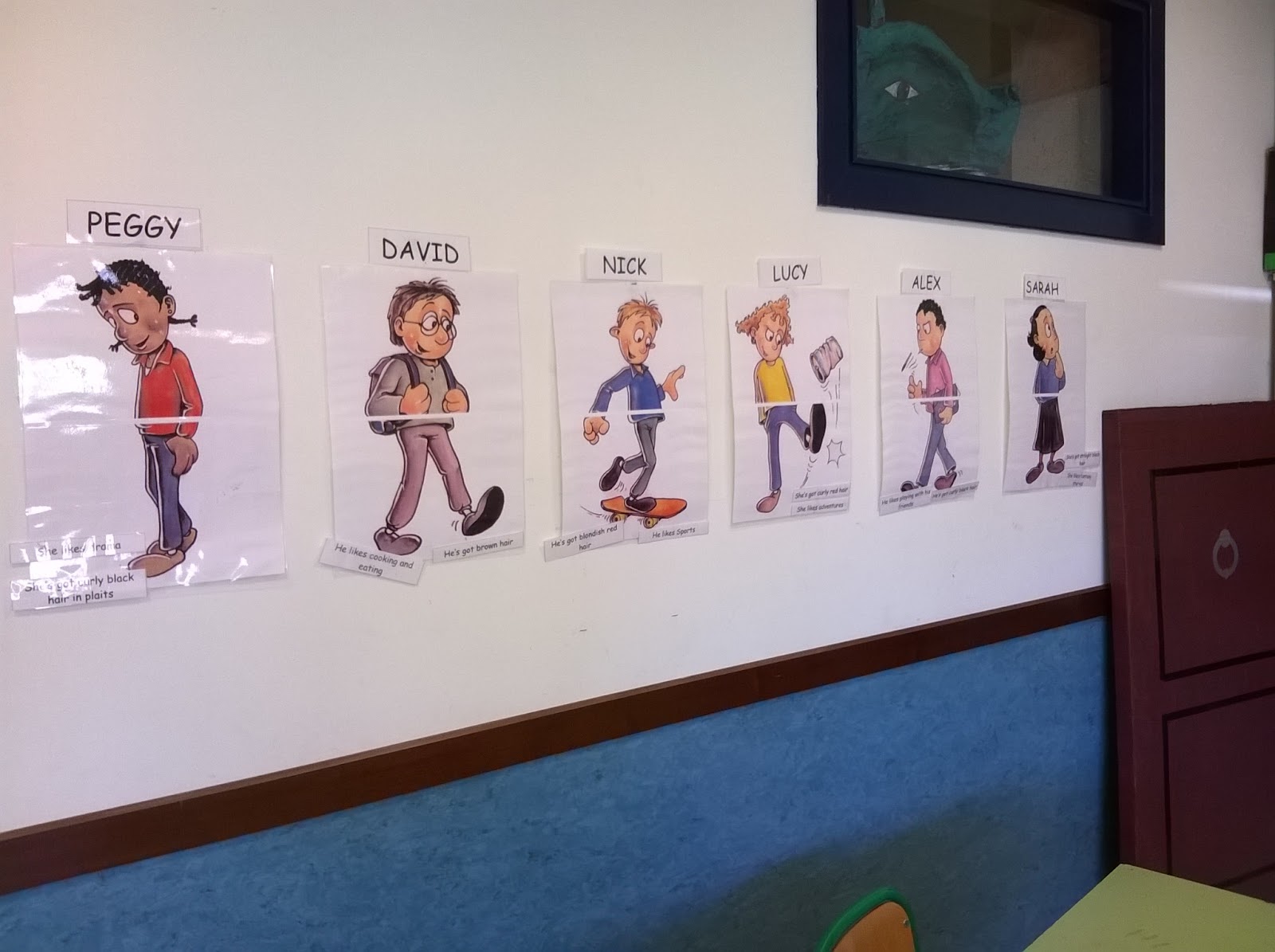

Characters from the reading books for LH4

Storage space to keep the reading books for all grades, LH1 to LH4

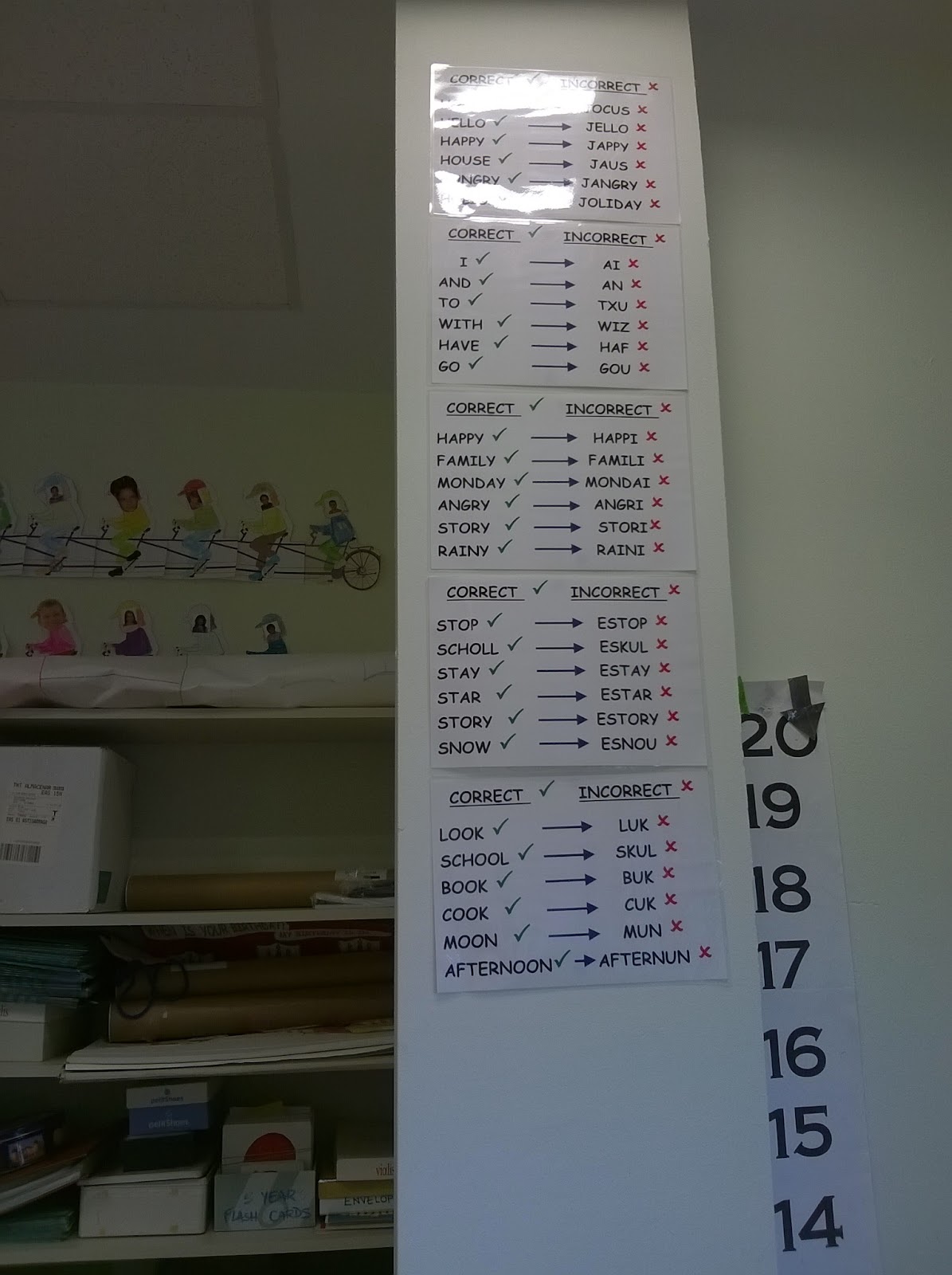

Spelling reminders on the wall

Even though Astigarraga Herri Eskola is a state-funded school, it follows the methodology set up by the fee-paying ikastolak: Artigal in HH and Eleanitz in LH. I have been taking notes about all the activities that we do in each lesson, but writing them all would be too long. Instead, I will write the things that have struck me the most in these first days.

Both Artigal and the Eleanitz material for LH use stories to structure lessons. Each academic year comprises six stories/units, so each story takes roughly six weeks. Right now, all groups in HH and LH are in the second story.

In LH, the routines at the beginning of the lesson are the same for all levels, although they are performed in a slightly different way. There is a helper each day who takes care of the routines and of handing out the coursebooks that are kept in the classroom. First, the helper says “good morning, everybody”, and the rest answer “good morning, x”. Then, the helper chooses a classmate to pose the first question (classmates who want to ask raise their hands), which is always the same: “what day is it today?”. The helper looks up the name of the day of the week, the date on the calendar, and the name of the month and the year. Depending on the age, the helper will copy or write the whole date on the board, or just the name of the week and the month. Then, it is time for the second question: “what’s the weather like?”, and the helper chooses the icon and says rainy or partly cloudy, or whatever. The third question is “who is missing?”, and the fourth question is “how are you?” (four choices: happy, sad, angry or tired, and the older ones add why they are feeking that way using “because…”). After that, the teacher sometimes will ask other children how they are feeling and why, and they have to answer “because…”.

I find these routines quite repetitive, assuming they are kept the same all year and every year, to be honest. Besides, they don’t add much to the routines children do in their regular classroom in Basque. It would be nice to at least change the order of questions in the higher levels, to test if children really understand the questions, or they just guess by the order. Nevertheless, routines take little time.

I have noticed that in LH sometimes they do an activity in just one small group (a role play, or a game), but only 4-5 children out of 25 get that chance to perform it. The rest are expected to sit quietly and watch, which is a quite unrealistic expectation. I don’t see what the rest can learn out of it, and I think I would try to implement ways to have all children performing the activity, even if that means the teacher will not be able to monitor everyone all the time. I think that, overall, that would improve their chances of learning. Besides, the younger ones find it really hard to bear such a long time being inactive, and they inevitably start to misbehave (that happened this morning in the LH1 lesson, where we ended up with most children having done no other task but sing one short song in a 45 minute lesson).

In the HH lessons, I encountered a totally Audiolingual activity, performing a dialogue with finger puppets, where children repeated the parts of each character. They are very short dialogues, so children can maintain their attention with no trouble. Of course, handing out the envelopes which contain each children’s puppets, taking them out of the envelope and putting them on their fingers takes much longer than performing the play, but children are practising other skills meanwhile, so I think it is ok.

There was one shocking thing in the puppet stories, though: the two I have listened to so far end up with a choice that the main character has to take (put the biscuit in the mouth or in the box, eat the much hated fish or feed it to the cat), and depending of which choice each child does, the teacher will ask them to come forward and either say “good boy/girl” and give them a kiss, or say “naughty boy/girl” and spank them saying “smack, smack”. Now, this spanking I didn’t like at all, I must say. It is obviously a game, and children like it, but it isn’t consistent with the message that is given to children in HH about not hitting others. When I told the teacher about my doubts on it, she said that she found it awkward too, and that one child had spanked her while she was doing it in class, and she had to tell them that that wasn’t allowed (telling a 4-5-year-old in English that they shouldn’t do what they just watched the teacher doing…).

During the week, I have made a copy of the Artigal material (one CD and 3 DVDs), and I have been reading the explanation on the principles of this method and how the stories should be performed. After having read it, I see that what seemed an Audiolingual activity to me is quite something else, as children don’t just repeat everything they have heard. When the teachers performs the story, depending on the place where they stand they will be one character or another, so children understand the plot and repeat what each character says, but not what the teacher says when standing in a neutral position and acting as a narrator who gives the word to each character (e.g. “and then the little girl said…”).

Once I get a bit used to Artigal, I plan on starting to take over my teacher in small tasks, such as performing the finger puppet dialogue, or performing the storytelling, so I start practising a bit. Both my tutor and the HH English teacher are very nice. Particularly the HH teacher has encouraged me to start practising in class and has told me that I can start whenever I feel ready for it. So far, I have been sitting beside her (except if some children in the group need an adult by their side to focus attention, when I have been sitting by them), and doing everything she does. As children are usually the most open minded kind of humans you can find, they have accepted me fine.

Next week I will start analysing the LH material, which seems to consist on one activity book and one reading book per student in each grade, plus the teacher’s guide and CDs with the listening material.

English teachers need to have an awful lot of things in their mind: they have to learn a lot of names (there are 17 to 26 children in each group and three groups in each grade), they have to memorise the dialogues, songs and rhymes of the story they are working on with each grade, and they have to keep track of how far they have gone with each of the three groups in the grade. Compared to the regular tutor work I experienced in my previous two in-school trainings, it is much harder on that side, I have to say.

Well, I think this is enough for my first week. Next week I will write about the sort of tasks performed in LH mainly.

2014/11/12

Things we learned in our mini-lesson presentations

First of all, the main learning I would underline is how important it is to write down your lesson planning, because when you actually write it you realise many things about the activities you intend to develop. Planning helps to find mistakes and things which can be improved, and it also helps to act more freely during the lesson, because you follow a guideline that you have made yours before. You are much more likely to feel relaxed and therefore you will help create a nice atmosphere.

The second learning I got out of last week's mini-lessons is that you should try to work in a team. There is no way any of the four of us would have been able to come up with the ideas and activities we included in our mini-lesson working on their own. Ours was a proposal made in a group and the four of us contributed equally to it. Working collaboratively is a key element if you want to have a sound proposal for your lessons.

There were many other learnings, which I will just mention briefly: the importance of thinking carefully the instructions the teacher will give for learners to perform tasks; trying to avoid competition among learners, as it rarely helps create a good atmosphere; bearing in mind that we can use activities we designed in previous years for maths, sciences, history etc. in the English class; using drawings to synthesise what has been learned and as a guideline to communicate those contents to others; using games; grading the task, and not the text, in task-based learning using texts; thinking of ways to make all learners participate; being aware of the interaction pattern you are promoting and trying to get the focus on students; thinking of small things (realia, materials...) which will help create the situation where you intend learners to visualise themselves in; using the information gap resource to motivate learners so they will listen to each other; using flashcards and stickers to help learners create meanings in the target language, rather than using translation into L1; thinking of activities that learners will enjoy, and will be challenging at the same time.

The second learning I got out of last week's mini-lessons is that you should try to work in a team. There is no way any of the four of us would have been able to come up with the ideas and activities we included in our mini-lesson working on their own. Ours was a proposal made in a group and the four of us contributed equally to it. Working collaboratively is a key element if you want to have a sound proposal for your lessons.

There were many other learnings, which I will just mention briefly: the importance of thinking carefully the instructions the teacher will give for learners to perform tasks; trying to avoid competition among learners, as it rarely helps create a good atmosphere; bearing in mind that we can use activities we designed in previous years for maths, sciences, history etc. in the English class; using drawings to synthesise what has been learned and as a guideline to communicate those contents to others; using games; grading the task, and not the text, in task-based learning using texts; thinking of ways to make all learners participate; being aware of the interaction pattern you are promoting and trying to get the focus on students; thinking of small things (realia, materials...) which will help create the situation where you intend learners to visualise themselves in; using the information gap resource to motivate learners so they will listen to each other; using flashcards and stickers to help learners create meanings in the target language, rather than using translation into L1; thinking of activities that learners will enjoy, and will be challenging at the same time.

Things I like from several foreign language teaching methods

The review we did last week on the ten methods and approaches for learning and teaching languages we have been working on along the term gave me the perfect chance to pick concepts and ideas I like the most from each. As Diane Larsen-Freeman states in her book titled Techniques and Principles in Language Teaching, we don't need to agree with every principle of a certain method; we could just take some techniques or principles linked with it which we feel that fit into the idea of language teaching we are trying to build during this Minor.

So, for now, I would say that these are the things I have found attractive and useful in each method:

So, for now, I would say that these are the things I have found attractive and useful in each method:

- Grammar translation method: I liked the focus on culture and literature linked with the target language. I also think that working on synonyms and antonyms could be useful in some situations, because as we have learned in psycho-motricity, the notion of contrast is a powerful resource for learning, and synonyms and antonyms are about similarity and contrast in language.

- Audio-lingual method: I liked the fact that it works mainly on listening and speaking skills at the beginning. I also like the importance given to input quality, and the fact that errors are corrected immediately. The use of minimal pairs can be useful too, as it focuses on contrast and can help learners become aware of phonemes in the target language which might be hard to discriminate. The fact that students have an active role, even though the interaction is teacher-directed, is a plus too.

- Silent way: I find the notion of silence as a teaching tool very interesting, because it draws our attention to the interaction pattern and the need to weight carefully when the teacher should speak. Thinking of ways to be an active teacher using resources other that speaking is challenging too. The fact that students are encouraged to be autonomous learners is also interesting. I also like the idea of students working cooperatively and becoming highly involved in the activities. I find linking language learning to problem solving, and seeing it as a guided discovery very interesting too.

- Suggestopedia: The fact that it takes into account the role of students' feeling in the learning process is one of the main points I like. Therefore, creating a nice atmosphere will improve learning. I also liked the use of direct and indirect positive suggestions, and the fact that we can take advantage of peripheral learning. Adopting a new identity and singing songs as tools to loosen up and reach a state in which we will be more open to learning is also attractive.

- Community language learning: I like the fact that the role of the teacher evolves along the learning process in a way which resembles scaffolding. I also like the importance given to psychology, the active role of learners and the focus on building a community of learners who will support each other. Learning in a laid back atmosphere, through natural conversations which follow learners' interests is also an interesting idea. Enabling learners to produce right from the beginning can also be a very good way to improve motivation and, obviously, working in small groups would be ideal too.

- Total physical response: I like very much the notion of enjoying while we learn and the fact that the learners starts to produce when they feel ready for it. Regarding non-verbal responds done with body movements as a way of production will also be encouraging for learners. Besides, learning through movement and action fits very well with the way children learn, especially in pre-primary.

- Communicative approach: I like that fact that it adds more competences to the grammatical competence taken into account by the traditional methods mentioned so far (sociolinguistic, strategic and discourse competences). Placing learners in real life situations where language becomes the tool to solve a problem is also very interesting. The fact that activities need to be meaningful for learners, and that both teacher's goals and students' goals need to be taken into account is also important. The focus on interaction among students, using authentic materials, games and role play are powerful ideas too.

- Natural way: I like the focus on everyday life vocabulary and situations, the stress on having a nice atmosphere, the notion of i+1 (input a bit above of what the learner has already achieved), and the use of realia, gestures, total physical response, games, stories and songs. Since it is based on the way we naturally learn language, it can be very appropriate for pre-primary, bearing in mind that we will by no means have the amount of exposure needed to learn language using this method only.

- Process programme (task based learning), and CLIL: setting real life situations which students might encounter in life, where a natural context for language use is provided sounds like the right thing to do. Language becomes the tool to deal with the situation, in a problem-solving context. I also like very much the idea of focusing on the process, instead of the final outcome. Placing the focus on students, having tasks which are meaningful for learners, transcending the classroom walls and working on a topic or project for several weeks are also very interesting ideas in my opinion. The notion of acquiring language at the same time as we build knowledge on diverse topics fits in very well with the way teaching and learning are approached in pre-primary, so it is very useful.

Friends or foes?

Being placed together with primary education students in the Minor is a great opportunity to learn new things, no doubt. It gives you the chance to see how others see education, their aims, their ways of doing. I have the feeling that us, pre-primary education students, are more homogeneous that our primary education classmates. Maybe it is just because we are much less, so there isn't a chance for much diversity among us. We share similar values and approaches to education.

I guess there could be a more polite way to put it, but since this is mainly for myself to read, I will be quite blunt: us, pre-primary education students, believe that many of our primary education classmates act in favour of the traditional school in general. We are beginning to repeat the pattern we have experienced in our previous in-school trainings: primary teachers think that children are not "prepared enough" when they finish pre-primary, and pre-primary teachers feel that primary teachers are only concerned about contents.

One of my group mates in the mini-lesson we have recently prepared explained it very clearly: we should have HH6, HH7, HH8... instead of LH1, LH2, LH3..., meaning that the ways of doing and the principles of pre-primary should be fed into primary education (taking into account the developmental differences among children in both stages, of course). I have the feeling that the traditional school has managed to survive in primary and secondary education, while it has been wiped out in pre-primary and university. But this is just a feeling which could well be due to my prejudice, and being as we are together, it would be great if we could discuss this openly.

I guess there could be a more polite way to put it, but since this is mainly for myself to read, I will be quite blunt: us, pre-primary education students, believe that many of our primary education classmates act in favour of the traditional school in general. We are beginning to repeat the pattern we have experienced in our previous in-school trainings: primary teachers think that children are not "prepared enough" when they finish pre-primary, and pre-primary teachers feel that primary teachers are only concerned about contents.

One of my group mates in the mini-lesson we have recently prepared explained it very clearly: we should have HH6, HH7, HH8... instead of LH1, LH2, LH3..., meaning that the ways of doing and the principles of pre-primary should be fed into primary education (taking into account the developmental differences among children in both stages, of course). I have the feeling that the traditional school has managed to survive in primary and secondary education, while it has been wiped out in pre-primary and university. But this is just a feeling which could well be due to my prejudice, and being as we are together, it would be great if we could discuss this openly.

2014/11/06

Contents. How much should children know when they finish school? What do teachers need to know when they graduate?

In the last lessons the word "contents" has been mentioned more than once, implying that some activities might not have "enough contents" or didn't deal with the "right or usual contents" for the primary or pre-primary classroom. I have also heard some of my classmates complain that we haven't been "taught" enough during the degree, that our teachers could have taught us so much more than what they have. Not enough contents, it seems.

On the other hand, now, more than ever, contents are everywhere, just a click away. So, what do we need contents for? Why do we need to store them in our minds? Which contents? How many? What are contents, after all? Are contents the matter of which knowledge is made of? A proof that learning has been achieved? A means to build learning?

Many questions, and little answers; that is what I have. But one thing I have learned so far: learning how to think and learn is the most important learning; maybe the only learning we should pursue in education. Those who know how to think and how to learn will sure find the appropriate contents for their purposes. As far as I see it, contents are often by-products of knowing how to think and learn. I am not very interested in contents as such, but in what is behind them. The official Basque curriculum we have worked on several times during our degree states it clearly: skills or competences are our goal, and contents are aspects we work on in order to achieve those skills. Their purpose is to offer opportunities to develop last longing skills which will remain even after the details of specific contents are somehow forgotten.

To me, this blog is a tool to store contents in such a way that they will be easy to retrieve for me when I forget their details. Those contents have been in my mind and left a trace in my actions and my thoughts, but I cannot have them all in the front of my brain with full detail at the same time. I find that the blog is a great tool to "extend my brain" as it were, because it is organised in a way which makes sense to me. It reflects my interests and my values; my struggles and my conflicts. At the end of the day, it illustrates my learning process, as those who know about this sort of tools say.

Yet, it is true that a teacher needs to know some contents; those which are relevant to their profession. Contents will be regarded as relevant if they are included among the required knowledge by those who design the education system and curricula, also if they are deemed to be of importance to our teachers, and each one of us will be free to choose contents which seem relevant to ourselves, depending on our interests and values. So, relevant contents for teachers are set at different levels, and each teacher has some autonomy on the matter, as well as some requirements to fulfill.

But we cannot rely on contents being at hand. For example, if inclusion is important to us, we will need to know what kind of grouping favours inclusion and follow those criteria at the specific moment of deciding on grouping in a classroom. We will not be able to look it up later on. So, some contents need to be integrated into our thinking, into our decision making; otherwise, they will not be useful at all. But some other contents are not essential, as I argued when I mentioned the Reggio Emilia style project where the teacher learned about nature along with students. Of course, if the teacher knows about nature they will be able to guide students much better, but even if they don't, as long as they know how to promote learning about dealing with things one doesn't know about, it will be fine.

I found a piece of news which fits perfectly into what I am trying to explain, that gave some examples of questions that undergraduate students taking admission interviews at Oxford have to answer to. Questions such as: "An experiment appears to suggest Welsh speakers are worse at remembering phone numbers than English speakers – why?", or "How much of the past can you count?", or "If you could save either the rainforests or the coral reefs, which would you choose?". These questions are designed to see how students respond to something which is unknown to them, to assess their thinking skills. You can read some of the answers interviewers would expect.

Does that mean that Oxford undergraduates are not supposed to know "regular contents"? Well, of course not. Apparently, students applying at Oxford and Cambridge will be required to score two elite A* grades at their A-level exam, but besides proving they know their contents, they will also have to prove they can use them in a creative way. I must say I can't agree more with the approach, although there is a very worrying fact mentioned in the last article, which reports that public school students in the UK (that is, students from very prestigious and expensive private schools) do much better that state-funded school students at these admission tests. Provided we fix that big problem, I'd say that is the sort of learning I would like to promote among children (and adults, of course).

On the other hand, now, more than ever, contents are everywhere, just a click away. So, what do we need contents for? Why do we need to store them in our minds? Which contents? How many? What are contents, after all? Are contents the matter of which knowledge is made of? A proof that learning has been achieved? A means to build learning?

Many questions, and little answers; that is what I have. But one thing I have learned so far: learning how to think and learn is the most important learning; maybe the only learning we should pursue in education. Those who know how to think and how to learn will sure find the appropriate contents for their purposes. As far as I see it, contents are often by-products of knowing how to think and learn. I am not very interested in contents as such, but in what is behind them. The official Basque curriculum we have worked on several times during our degree states it clearly: skills or competences are our goal, and contents are aspects we work on in order to achieve those skills. Their purpose is to offer opportunities to develop last longing skills which will remain even after the details of specific contents are somehow forgotten.

To me, this blog is a tool to store contents in such a way that they will be easy to retrieve for me when I forget their details. Those contents have been in my mind and left a trace in my actions and my thoughts, but I cannot have them all in the front of my brain with full detail at the same time. I find that the blog is a great tool to "extend my brain" as it were, because it is organised in a way which makes sense to me. It reflects my interests and my values; my struggles and my conflicts. At the end of the day, it illustrates my learning process, as those who know about this sort of tools say.

Yet, it is true that a teacher needs to know some contents; those which are relevant to their profession. Contents will be regarded as relevant if they are included among the required knowledge by those who design the education system and curricula, also if they are deemed to be of importance to our teachers, and each one of us will be free to choose contents which seem relevant to ourselves, depending on our interests and values. So, relevant contents for teachers are set at different levels, and each teacher has some autonomy on the matter, as well as some requirements to fulfill.

But we cannot rely on contents being at hand. For example, if inclusion is important to us, we will need to know what kind of grouping favours inclusion and follow those criteria at the specific moment of deciding on grouping in a classroom. We will not be able to look it up later on. So, some contents need to be integrated into our thinking, into our decision making; otherwise, they will not be useful at all. But some other contents are not essential, as I argued when I mentioned the Reggio Emilia style project where the teacher learned about nature along with students. Of course, if the teacher knows about nature they will be able to guide students much better, but even if they don't, as long as they know how to promote learning about dealing with things one doesn't know about, it will be fine.

I found a piece of news which fits perfectly into what I am trying to explain, that gave some examples of questions that undergraduate students taking admission interviews at Oxford have to answer to. Questions such as: "An experiment appears to suggest Welsh speakers are worse at remembering phone numbers than English speakers – why?", or "How much of the past can you count?", or "If you could save either the rainforests or the coral reefs, which would you choose?". These questions are designed to see how students respond to something which is unknown to them, to assess their thinking skills. You can read some of the answers interviewers would expect.

Does that mean that Oxford undergraduates are not supposed to know "regular contents"? Well, of course not. Apparently, students applying at Oxford and Cambridge will be required to score two elite A* grades at their A-level exam, but besides proving they know their contents, they will also have to prove they can use them in a creative way. I must say I can't agree more with the approach, although there is a very worrying fact mentioned in the last article, which reports that public school students in the UK (that is, students from very prestigious and expensive private schools) do much better that state-funded school students at these admission tests. Provided we fix that big problem, I'd say that is the sort of learning I would like to promote among children (and adults, of course).

2014/11/02

Measuring my participation

In the past few weeks I have been considering what my participation should be like. I have been thinking that we don't get that many chances to practise our speaking skills in public, and since we will be assessed on that at the end of the year in several way (dissertation presentation, unit assessments, oral exam), I should contribute to offer a chance to practise to other classmates who might need it more than me. So, now I try to wait until others answer to questions or give their opinions, and only if I feel something important for me hasn't been said, especially if it is about something any of us has done well, will I talk. I don't always succeed, because I tend to get carried away and I find most of the things we learn about absolutely fascinating.

I have also noticed, or at least that is my feeling, that people are participating less and less in class. Maybe it is because we are a bit tired with quite a few assignments. This is being a short but intense term, and things don't have enough time to sink in, that is my feeling, at least. I like to ruminate on our learnings, savouring them, but this year there is no chance of doing that, unfortunately.

I had hoped for a last year where we would be realising how much we had learned and putting it into practise, but without trying to stuff our brains with new things. Acquiring content and language at the same time is a big effort. And when we see that our former classmates who chose the other Minors will be having a whole week off on the 10th week, while we take two exams and a language diagnosis, we can't help but think that we are losers. Hopefully, later on we will be happy about that choice we made. Personally, I know I would have enjoyed any of the other Minors just as much, and if I weren't a working student I would've tried to take more than one, if you are allowed to do so. But in my situation, one Minor will be more than enough!

I have also noticed, or at least that is my feeling, that people are participating less and less in class. Maybe it is because we are a bit tired with quite a few assignments. This is being a short but intense term, and things don't have enough time to sink in, that is my feeling, at least. I like to ruminate on our learnings, savouring them, but this year there is no chance of doing that, unfortunately.

I had hoped for a last year where we would be realising how much we had learned and putting it into practise, but without trying to stuff our brains with new things. Acquiring content and language at the same time is a big effort. And when we see that our former classmates who chose the other Minors will be having a whole week off on the 10th week, while we take two exams and a language diagnosis, we can't help but think that we are losers. Hopefully, later on we will be happy about that choice we made. Personally, I know I would have enjoyed any of the other Minors just as much, and if I weren't a working student I would've tried to take more than one, if you are allowed to do so. But in my situation, one Minor will be more than enough!

More lesson planning

Last Friday we continued with our lesson planning. First, we watched a video of two former students who brought children (now, that is real realia!) to their lesson presentation. Besides, it was a very interesting presentation, because they showed several English children's games. Apparently, these students listened to their classmates' concerns on how little they knew about games to use at school, in the playground during break time, so they organised a lesson around that topic. Now, that is a really nice thing to do for your classmates (and yourself).

The video also served as an introduction to what our presentations will be like at the end of the year, after we come back from our in-school training period, when we will also have real children. That will be great, because we will be able to see with our own eyes if our ideas work or not. I can't wait!

Oh, and I already have a guinea-pig volunteer; yesterday afternoon I saw my 6-year-old niece, and she showed me her new classroom's windows from the outside (she just started primary in a different location, but in the same school). So, I told her I might ask her teacher for permission to come one day (I did my two in-school trainings at her school), and then she remembered she came to university last year, when our psycho-motricity teacher gave us the chance to bring our in-school training class to university. She wasn't in my class, but since I knew she would love to come, I asked the teachers and herself, and she came along with "my" class. Well, yesterday she said that she would like to come to my "school" again, and that she is going to ask her teacher if they can come. Obviously, I told her that I also needed to ask my teachers for permission. So, if we happen to be short on primary first children, I have a very enthusiastic volunteer willing to recruit her class!

The video also served as an introduction to what our presentations will be like at the end of the year, after we come back from our in-school training period, when we will also have real children. That will be great, because we will be able to see with our own eyes if our ideas work or not. I can't wait!

Oh, and I already have a guinea-pig volunteer; yesterday afternoon I saw my 6-year-old niece, and she showed me her new classroom's windows from the outside (she just started primary in a different location, but in the same school). So, I told her I might ask her teacher for permission to come one day (I did my two in-school trainings at her school), and then she remembered she came to university last year, when our psycho-motricity teacher gave us the chance to bring our in-school training class to university. She wasn't in my class, but since I knew she would love to come, I asked the teachers and herself, and she came along with "my" class. Well, yesterday she said that she would like to come to my "school" again, and that she is going to ask her teacher if they can come. Obviously, I told her that I also needed to ask my teachers for permission. So, if we happen to be short on primary first children, I have a very enthusiastic volunteer willing to recruit her class!

Lesson planning

Last Thursday we devoted the lesson to our next week's mini-lessons. First, our teacher showed us some examples of lesson planning from previous years, so we could have a model of what we are supposed to do (yes, we also receive modelling as part of the scaffolding of our learning!).We also watched pictures and videos of past presentations, which were very interesting.

Our teacher reminded us that a collection of activities is not a lesson (horror faces in the audience), she advised us to go from less demanding (both linguistically and cognitively) to more demanding activities within the lesson, to make sure all activities are connected, and to make sure that all activities pursue relevant aims. I think that was the point where we all thought "Gee, shouldn't we have started from here, instead of from designing our activities like we have been doing during the week?". Well, nothing to worry about! It doesn't necessarily have to be done bottom to top, or top to bottom, as long as you make sure you go back and forth from teaching objectives to tasks to be performed by students a few times during your lesson preparation process. Just like in the learning process, some prefer to go from the detail to the big picture, and some others go from broad concepts to concrete aspects. Personally, I need to make sure I go back and forth a few times, but I am flexible as to the starting point. Of course, one needs to bear in mind that young children go from concrete experience to global concepts.

After that introduction by our teacher, we continued designing our activities. In our case, we decided that since we were only two days away from our presentation, we would not make any dramatic changes, and in a quick assessment we reached the conclusion that we were not that far away from what would be asked from us. So, we continued writing the central column of the lesson planning chart, that is, the description of our tasks and procedures.

Our teacher reminded us that a collection of activities is not a lesson (horror faces in the audience), she advised us to go from less demanding (both linguistically and cognitively) to more demanding activities within the lesson, to make sure all activities are connected, and to make sure that all activities pursue relevant aims. I think that was the point where we all thought "Gee, shouldn't we have started from here, instead of from designing our activities like we have been doing during the week?". Well, nothing to worry about! It doesn't necessarily have to be done bottom to top, or top to bottom, as long as you make sure you go back and forth from teaching objectives to tasks to be performed by students a few times during your lesson preparation process. Just like in the learning process, some prefer to go from the detail to the big picture, and some others go from broad concepts to concrete aspects. Personally, I need to make sure I go back and forth a few times, but I am flexible as to the starting point. Of course, one needs to bear in mind that young children go from concrete experience to global concepts.

After that introduction by our teacher, we continued designing our activities. In our case, we decided that since we were only two days away from our presentation, we would not make any dramatic changes, and in a quick assessment we reached the conclusion that we were not that far away from what would be asked from us. So, we continued writing the central column of the lesson planning chart, that is, the description of our tasks and procedures.

2014/11/01

Back in the pre-primary classroom and analysing the curriculum

The Friday before last we started our lesson as if we were in a pre-primary classroom. Our teacher even chose a helper to go over the daily routines and we sang and danced to a good morning song. Our teacher linked this first song with another one asking us if we felt happy after having started with a song, so we sang and danced to another song on what people do when they are happy.

It felt great to go back to the pre-primary classroom, and it was interesting to watch some reactions. The pre-primary education classmates that I had around were as thrilled as me, whereas I thought I heard someone saying "pathetic!" behind me among primary education classmates. I have the feeling they are not as used as we are to playing silly. By the way, playing childish was one of Suggestopedia's principles; this method argues that infantilization is a good resource for language learning, as it frees our mind and takes away the hurdles we put in our own learning path.

Obviously, our teacher reminded us that although there are tons of materials available in the Internet nowadays, that doesn't mean they are all equally valuable. So, we need to be able to discriminate, always bearing our educational objectives in mind. This coming week we will have a chance to see how developed our discriminating skills are, because we will present our mini-English lessons in groups. Sticking to your objectives isn't easy at all; one can happily lose track while getting carried away with very attractive materials or flashy ideas for tasks. Besides, building your own criteria on education is not something you can improvise; it takes time and thinking.

Well, going back to our lesson that day, after feeling refreshed and full of energy acting childish, we split in small groups to talk about the Basque official curriculum, and its contents regarding language, especially English. I had read the goals and contents for pre-primary, and my groupmates had read the ones for primary. The main difference that we noticed between both was that pre-primary children will be working almost exclusively in their listening and speaking skills, while primary children will practice all four skills.

Like any other policy, the curriculum is a text open to a wide range of interpretations. For instance, it states that beginning to use a foreign language orally to communicate within usual situations in the classroom is the skill that should be developed in the 0 to 6 years stage. Therefore, we know that pre-primary children should only be expected to use the foreign language in its spoken form (although we cannot forget that beginning to know about the uses of written language is also a general aim for this stage), and that we should only expect for them to be able to communicate in situations very familiar to them where they will have a lot of support from the communicative context, what does "beginning" mean? where do we draw the line between having begun and not having so? how do we assess if the goal has been accomplished?

There is a wide controversy around the interpretation of the curriculum when it comes to reading and writing skills. The "beginning to know about the uses of written language" in pre-primary curriculum is interpreted as being able to read and write their name and surname, plus the names and surnames of all classmates, plus the names of each of the three courses they have for meal everyday, plus... So, the curriculum is stretched further and further away, and not because a teacher assesses the zone of proximal development and the motivation in a group and reckons that those learnings can be achieved in that particular moment, but because in that school (and most other schools) children are expected to know how to read and write by Christmas in their first year of primary.

The interpretation of "beginning" should be flexible enough to embrace all children who go to school, enable them to progress in their learning and make them feel good about themselves.

It felt great to go back to the pre-primary classroom, and it was interesting to watch some reactions. The pre-primary education classmates that I had around were as thrilled as me, whereas I thought I heard someone saying "pathetic!" behind me among primary education classmates. I have the feeling they are not as used as we are to playing silly. By the way, playing childish was one of Suggestopedia's principles; this method argues that infantilization is a good resource for language learning, as it frees our mind and takes away the hurdles we put in our own learning path.

Obviously, our teacher reminded us that although there are tons of materials available in the Internet nowadays, that doesn't mean they are all equally valuable. So, we need to be able to discriminate, always bearing our educational objectives in mind. This coming week we will have a chance to see how developed our discriminating skills are, because we will present our mini-English lessons in groups. Sticking to your objectives isn't easy at all; one can happily lose track while getting carried away with very attractive materials or flashy ideas for tasks. Besides, building your own criteria on education is not something you can improvise; it takes time and thinking.

Well, going back to our lesson that day, after feeling refreshed and full of energy acting childish, we split in small groups to talk about the Basque official curriculum, and its contents regarding language, especially English. I had read the goals and contents for pre-primary, and my groupmates had read the ones for primary. The main difference that we noticed between both was that pre-primary children will be working almost exclusively in their listening and speaking skills, while primary children will practice all four skills.

Like any other policy, the curriculum is a text open to a wide range of interpretations. For instance, it states that beginning to use a foreign language orally to communicate within usual situations in the classroom is the skill that should be developed in the 0 to 6 years stage. Therefore, we know that pre-primary children should only be expected to use the foreign language in its spoken form (although we cannot forget that beginning to know about the uses of written language is also a general aim for this stage), and that we should only expect for them to be able to communicate in situations very familiar to them where they will have a lot of support from the communicative context, what does "beginning" mean? where do we draw the line between having begun and not having so? how do we assess if the goal has been accomplished?

There is a wide controversy around the interpretation of the curriculum when it comes to reading and writing skills. The "beginning to know about the uses of written language" in pre-primary curriculum is interpreted as being able to read and write their name and surname, plus the names and surnames of all classmates, plus the names of each of the three courses they have for meal everyday, plus... So, the curriculum is stretched further and further away, and not because a teacher assesses the zone of proximal development and the motivation in a group and reckons that those learnings can be achieved in that particular moment, but because in that school (and most other schools) children are expected to know how to read and write by Christmas in their first year of primary.

The interpretation of "beginning" should be flexible enough to embrace all children who go to school, enable them to progress in their learning and make them feel good about themselves.

Multilingual education in the Basque Autonomous Community

1. Introduction

The Basque country is currently facing an important challenge: the transition from bilingual education to multilingualism. Previous learnings from the development of the bilingual education system, which started in the 1960’s, will prove useful to build a new framework for the introduction of foreign language learning while ensuring that Basque, a minority language, is maintained and its situation improved.

This document sums up the evolution of bilingual education in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC), briefly mentions the main resources that the Basque Government offers in order to support the system, summarises the projects and plans for multilingual education that have emerged in the last years, and outlines the main findings of research conducted on the subject.

2. Bilingual education and its evolution

Compulsory education in the BAC is divided into primary education (ages 6 to 12) and secondary education (ages 12 to 16). The early years stage (ages 2 to 6) is not compulsory, although most children attend school or nurseries at those ages. Further education (ages 16 to 18) is offered too. There are state-funded schools and fee-paying private schools in the BAC, and each account for approximately 50% of the total amount of students (Zalbide & Cenoz, 2008, p. 7).

In the 1960’s, during Franco’s regime, several private schools (“ikastolak”) were the starting point of Basque education. Although they were not recognised as official schools at first, their development forced the dictatorial regime to accept them. With the return of democracy, in 1979 Basque gained the official language status in the BAC, together with Spanish (Cenoz & Etxague, 2011, p. 34; Elorza, 2013, pp. 2–3; Gardner & Zalbide, 2005, pp. 56–57; Zalbide & Cenoz, 2008, pp. 7–8).

The Law for the Standardisation of the Use of Basque (1982) and its development through the Decree for Education (1983) set that both Basque and Spanish would be compulsory units in all schools in order to guarantee the possibility of having acquired both at the end of compulsory education, and established three schooling models (A, B and D) from which families could choose. The A model is a Spanish-medium model where Basque is taught as a second language for 3 to 5 hours a week, in the B model each of the two languages is used during approximately half of the school time, and in the D model Basque is the language of instruction and Spanish is taught as a subject for 3 to 5 hours a week (Cenoz & Etxague, 2011, pp. 34–35; Elorza, 2013, pp. 5–6; Gardner & Zalbide, 2005, pp. 58–59; Zalbide & Cenoz, 2008, pp. 8–9).

The 1983 Decree ceased to be in effect after the 1993 Basque Schooling Law was passed, which maintained the three models and gave the “ikastolak” the chance to either integrate into the public education system or in the private sector (Gardner & Zalbide, 2005, p. 59).

The D model has increasingly been chosen by families since the bilingual models were established, growing from 25% in the eighties to 80-90% nowadays (Cenoz & Etxague, 2011, p. 35; Elorza, 2013, p. 13; Zalbide & Cenoz, 2008, pp. 10–11). This has resulted in a considerable increase in the number of bilinguals in the BAC, growing from 528 521 in 1991 to 714 136 in 2001 (Elorza, 2013, p. 16).

The bilingual education system had to face several challenges from the beginning (Gorter, Zenotz, Etxague, & Cenoz, 2014, pp. 210–211; Zalbide & Cenoz, 2008, pp. 11–16), such as improving teachers’ proficiency in Basque, developing materials in Basque or the standardisation of Basque. Although a great deal has been done in those fields, the improvement of the use of the language and its quality remain as important goals still to be reached (Gardner & Zalbide, 2005, pp. 65–69). There is also growing debate on the adequacy of the three bilingual models in the light of the evolution that has been outlined here and new challenges brought by the introduction of a third (or fourth) language in schools (Gorter et al., 2014, pp. 211–214; Zalbide & Cenoz, 2008, pp. 16–19) due to the spread of English as a lingua franca (Jessner & Cenoz, 2007, pp. 156–157).

3. Services and resources offered by the Basque Government

Regarding material resources, besides developing school facilities, the Basque Government has given support to develop terminology (standardisation of Basque), offered grants to teachers so they could produce materials, subsidised the printing and translating costs (EIMA), controlled the quality of materials, catalogued them and awarded best practices (Elorza, 2013, pp. 7–11; Gardner & Zalbide, 2005, p. 59).

The improvement of teachers’ proficiency in Basque has been achieved through training programmes (IRALE) where teachers could benefit from a full-time paid leave in order to improve their linguistic skills. Those schools that chose to also received training and support to evolve from the A model to the D model (Gardner & Zalbide, 2005, pp. 59–60).

The Basque Government also issues guidelines regarding pedagogical, curricular and organisational aspects such as grouping children according to their language skills in Basque and Spanish, the choice of subjects to be taught in each language in the B model, as well as appropriate teaching methodologies (Gardner & Zalbide, 2005, pp. 61–63). Teachers at state-funded schools have access to training programmes (PREST GARA) and receive support from regional centres (BERRITZEGUNEAK) in order to improve their teaching skills (Elorza, 2013, pp. 7–10), whereas fee-paying private schools have their own consultants (Cenoz & Etxague, 2011, p. 41).

There are also programmes to promote the use of Basque (NOLEGA) and the Basque Institute for Research and Assessment in Education (ISEI-IVEI) is involved in the development and monitoring of the Basque education system (Elorza, 2013, p. 7).

4. Current projects and plans for multilingual education